Artists of the Cobra movement used their art to express their political views and shared ideals. Cobra and politics will show this through a number of works from the museum collection.

In 1948, shortly after the Second World War, the Cobra movement was born from the fusion between three different artist groups from three countries: Denmark, Belgium and the Netherlands. The Danish experimental artists, who had united in the journal Helhesten, were already thinking about future society and the role art could play in it in the 1930s. The overarching view of the Danish group, many of whose members had also joined the communist party, was thus a desire for an art not only for the people, but also by the people. In Belgium, the Surrealist-Revolutionary Movement emerged in 1947 in reaction to the surrealism of the French founder André Breton. The Belgians thought that this surrealism was not communistic and revolutionary enough. After the liberation, many artists in the Netherlands, who had often hardly been able to make art during the war, had an enormous desire for freedom. Many of them, looking for a new art language in an art world in which everything seemed possible, united in the Dutch Experimental Group.

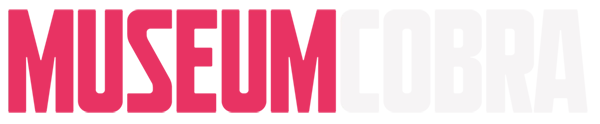

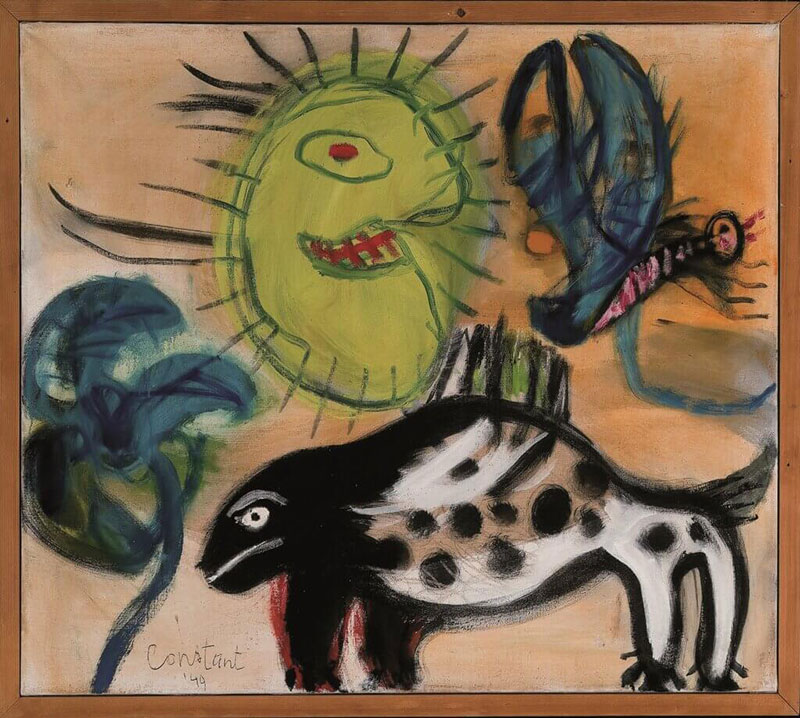

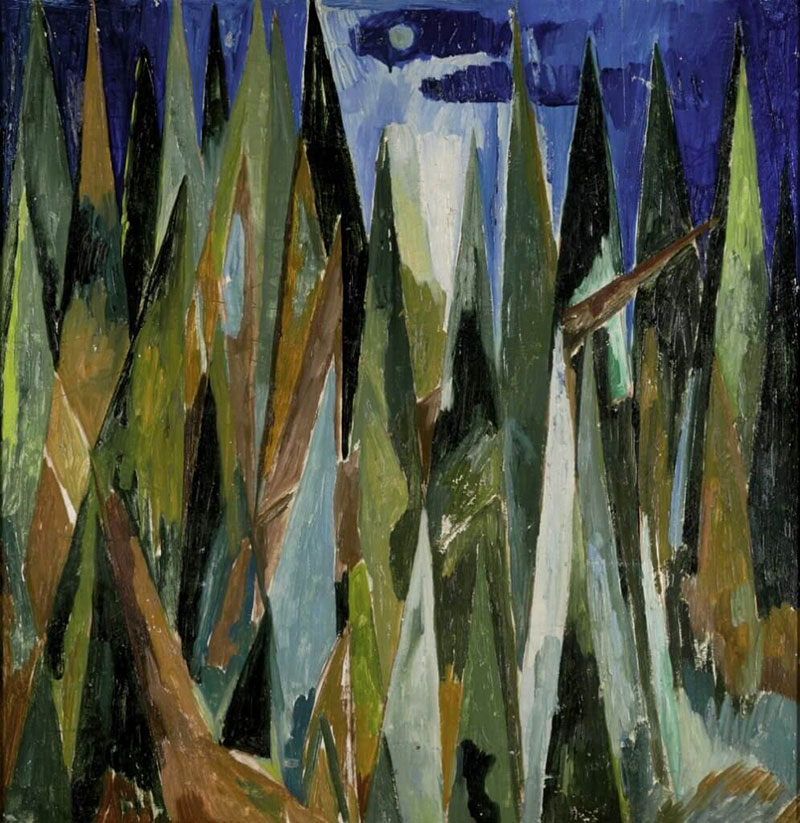

These three groups had shared ideas about what art was and what it should be in post-war society. Art had to be made for and by everyone. The Cobra artists hoped to remove the elitist aspect of art, so that creativity could be unleashed in all people. For them, art was not some inanimate object in a museum, but a place where people could connect, especially those who were excluded by the art world. These views were expressed in their works of art, for example because they found inspiration in fantasy, animals and art forms that were previously undervalued, such as non-Western art and children’s drawings.

Although almost all members of the Cobra group recognised themselves to a greater or lesser extent in the shared views, it was predominantly the group’s theorists, Asger Jorn, Christian Dotremont and Constant, who focused on art and society theories. Cobra and politics also shows that there were artists who had little to do with this, such as Karel Appel. The exhibition gives an overview of how the Cobra movement looked at art and society, and also pays attention to the politics of the group itself. What did it mean, for example, for a woman artist at that time to be part of this group or not to be part of it?

The exhibition can be seen in the museum at the same time as Frida Kahlo & Diego Rivera: A Love Revolution. The relationship between art and politics is discussed in both exhibitions.