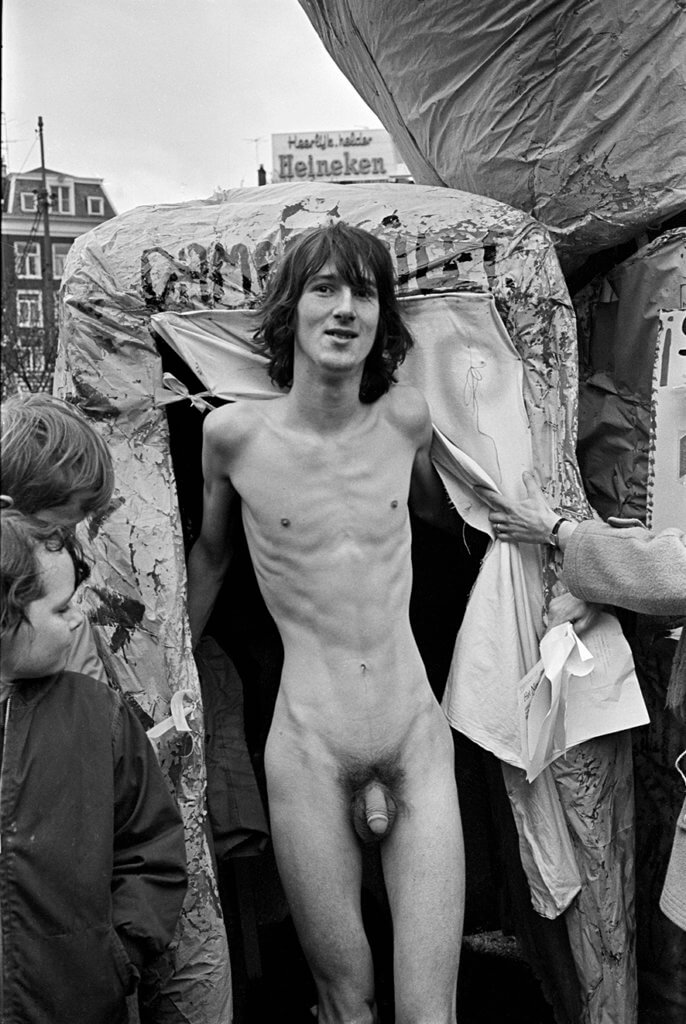

In the 1970s Eva Besnyö joined Dolle Mina. In recording the campaigns and demonstrations of this women’s movement, she put new principles into practice. From these works, it shows that she wanted to use her photographic work for social change. The series Dolle Mina is on show at the Cobra Museum, in relation to the work of Kati Horna en Ata Kando.

In the post-war period Eva Besnyö was involved in the foundation of the Gebonden Kunstenaars federatie (GKf), an art federation chaired by the later famous museum director Willem Sandberg, and was especially involved with the Department of Photography. Shortly after the bombing of Rotterdam, she photographed the city in ruins. She looked back at this with reticence: “I am still ashamed of that. Because they were beautiful pictures and you should not take beautiful pictures of devastation.” She thought a photograph should activate people. “After the war, I even distanced myself from the idea that photos should be beautiful. I had always beautifully lit and framed everything and I certainly didn’t want to continue with that super aesthetic work.” In the 1970s she joined Dolle Mina. In recording the campaigns and demonstrations of this women’s movement, she put her new principles into practice. From these works, it shows that she wanted to use her photographic work for social change. The series Dolle Mina is on show at the Cobra Museum, in relation to the work of Kati Horna en Ata Kando.

Eva Besnyö, raised in a Jewish intellectual family in Budapest, trained with József Pécsi. After completing her training, she left for Berlin, like Kati Horna, at the age of twenty, where she continued to learn the trade in photo studios. As an independent photographer she made portraits and reports, and was hired by the left-wing press agency Neofot. The rise of National Socialism in 1932 prevented her from working as a photographer and Besnyö decided to leave Berlin. She moved to Amsterdam.

In Amsterdam Besnyö worked for newspapers and press agencies. In the studio she made portraits and photographs of children. Outside of it she made reports and photographed architecture. Despite the outbreak of the Second World War, she was able to continue photographing until 1942. She was forced to go into hiding, but was given a false identity card that did not mention her Jewish background.