Kati Horna recorded as a photographer, numerous major historic events in the twentieth century. For her, being a photographer was a way of contributing to her political ideals while at the same time being able to lead an independent life as a woman. After major retrospective exhibitions in Mexico City, Madrid and Paris, this will be the first retrospective with works from Horna’s entire oeuvre in the Netherlands.

It was in October 1939 that the steamer De Grasse left the port of Le Havre, on its way to New York. The group of migrants on board had Mexico as their final destination. Since the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the Mexican government had supported the Spanish Republic and had welcomed a stream of newcomers. The 27-year-old photographer Kati Horna (Budapest, 1912 – Mexico City, 2000) was one of the migrants on board. In Mexico she was granted citizenship and she would stay there for the rest of her life. Horna’s flight to Mexico was one of the many journeys she made in her life. These had a major influence on her work.

Kati Horna was born in 1912 as Katalin Deutsch Blau in the then politically troubled Budapest. The violence, injustice and fear she was confronted with in her youth formed her as a photographer. Her stay in Berlin in 1931 was also a defining factor. Not only because of the threat of Hitler’s rule, but also because of her introduction to well-known Hungarian photographers such as Robert Capa (with whom she formed a lifelong friendship), László Moholy-Nagy and Simon Guttman. Eventually the rising threat of the Nazis became too severe; she left Berlin and went back to Budapest. She was privately trained by the then famous photographer József Pécsi who had her experiment with collages and photomontages. This early work by Horna was clearly influenced by the avant-garde movements of the 1930s.

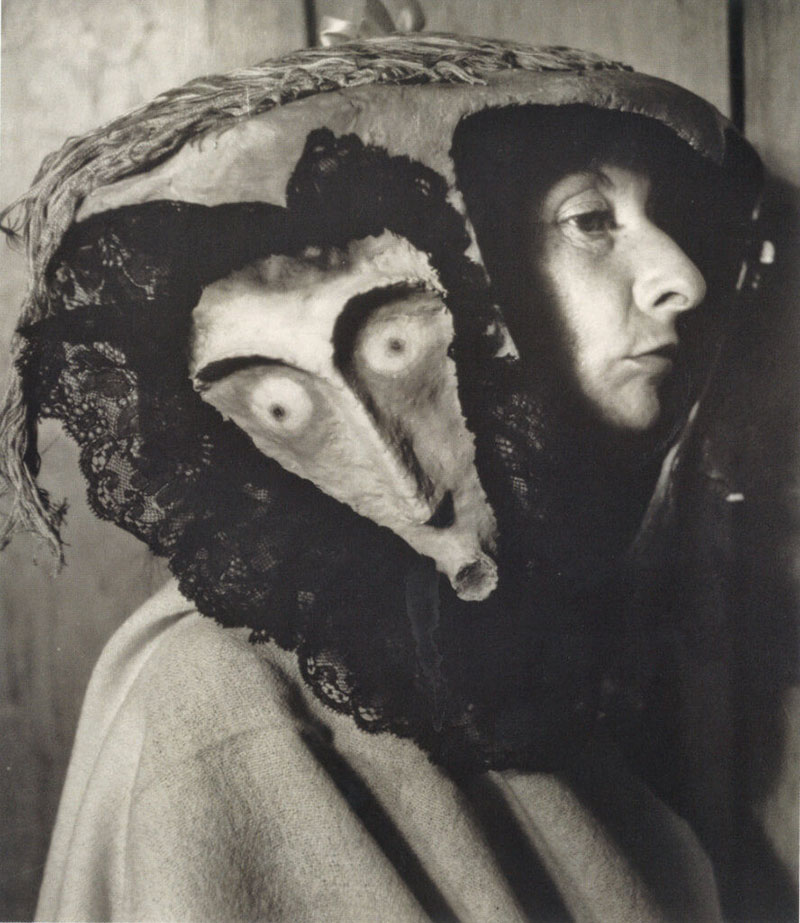

The regime of the fascist Hungarian dictator Miklós Horthy forced Horna to leave for Paris in 1933. Here, she continued to develop herself as a photographer, photographing the streets and cafés with her unique sense of irony and poetry. The birthplace of surrealism intensified her preference for poetic and staged images. It was only a few years later, however, that Horna gained great fame as a photographer through a propaganda commission from the Spanish Republican government. Between 1937 and 1939, she photographed the Spanish Civil War. As one of the few women on the front, she portrayed the Republican troops fighting against the dictator Franco. She was particularly fascinated by the consequences of the war on daily life, especially that of women and children. During this period Horna became editor of the Spanish magazine Umbral, where she met her future husband José Horna. Together with him she left for Paris after the civil war had ended. Here, Kati Horna started to photograph masks and dolls, which would remain recurring elements in her work.

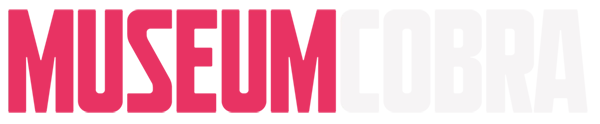

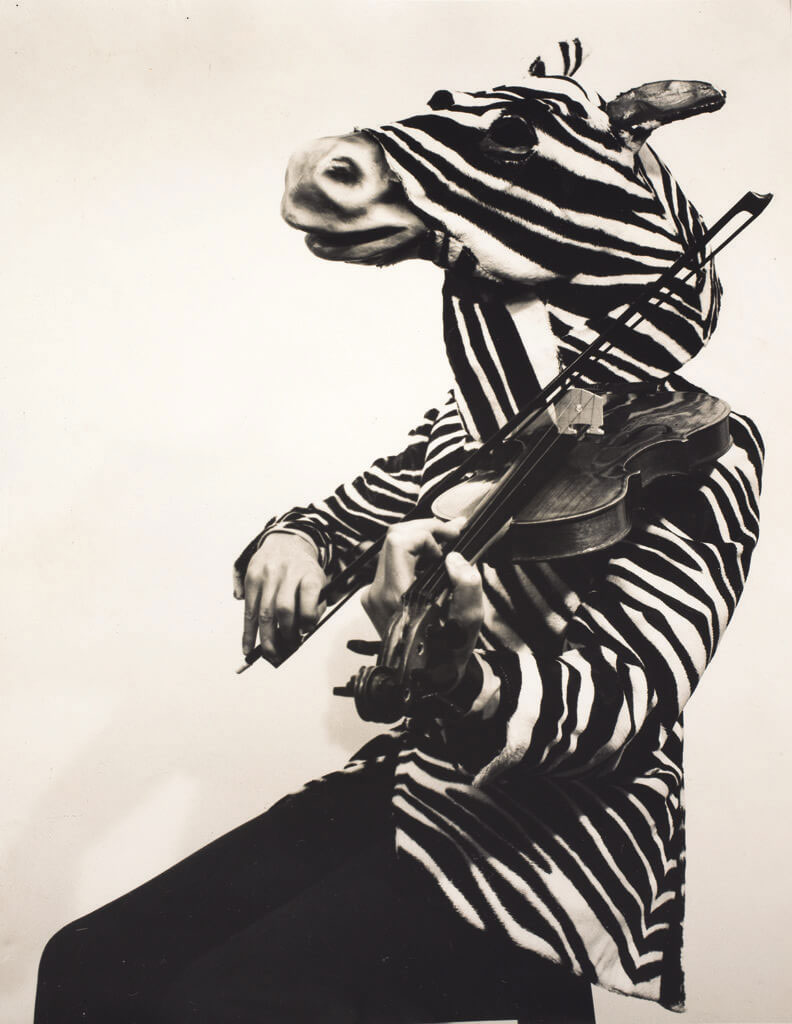

At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Kati Horna had to flee again. This time she and her husband fled to Mexico, where she continued her photography career. The art community in that country reluctantly welcomed the European intellectual migrants. The newcomers’ views on art were far removed from Mexican art, in which national pride played a major role. Nonetheless, Horna became one of the most active photographers of the city, and her photographs were widely published in newspapers and magazines such as El arte de cocinar, Seguro Social, Mexico This Month, Tiempo, S.nob and Diseño. She for example made reports about the abuses in psychiatric institutions, such as Nosotros (1944) and La Castañeda (around 1960). Her work also became more personal, documenting her experiences as a woman and feminist (Woman with Mask, 1962) and making a series about vampires (History of a Vampire: It Happened in Coyoacán, 1962). Meanwhile she had become active in various artistic and intellectual circles in Mexico, together with the surrealist artists Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, and sculptor and architect Mathias Goeritz.

Horna belonged to a generation of photographers who were forced to flee Hungary because of the massive insurrection against the Stalinist regime and the threat of the Nazis in the 1930s. This group also included Eva Besnyö (Hungary, 1910 – Netherlands, 2003) and Ata Kandó (Hungary, 1913 – Netherlands, 2017), both of whom would later settle in the Netherlands. Their work is shown in sub-presentations of the Kati Horna, Compassion and Engagement exhibition. These presentations show how these photographers also used their cameras as a political weapon for a better world.

As a photographer, Kati Horna always chose involvement with her subjects over artistic stardom. As a result, she has not become as widely known by the general public as her male contemporaries and compatriots Brassaï, Robert Capa, André Kertész and László Moholy-Nagy. The exhibition Kati Horna, Compassion and Engagement contributes to the international recognition of a versatile, socially engaged and humanist photographer who possessed great artistic creativity, and who has been of great importance to photojournalism.

This exhibition has been made possible with the collaboration of the Kati & José Horna archive, Mexico City, Dutch Photo Museum, Rotterdam and the Maria Austria Institute

All photos: Colección Archivo Privado de Fotografía y Gráfica Kati y José Horna © 2005 -2018 Ana María Horna y Fernández.